Deaths and hunger strikes point to mental health crisis on stranded cruise ships

The cruise ship Regal Princess docked in Rotterdam last Wednesday. On Sunday a Ukrainian woman is thought to have taken her own life by jumping overboard, Photograph: Robin Utrecht/Rex/Shutterstock

As tensions rise over failure to repatriate workers, plight of crews highlighted by the apparent suicide of a Ukrainian woman in Rotterdam

Patrick Greenfield and Erin McCormick-

Patrick Greenfield and Erin McCormick-

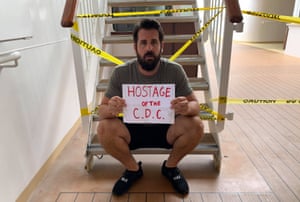

Several deaths, a hunger strike and disturbances on board cruise ships have raised fresh concern about what crew members say is the deteriorating mental health of staff stranded aboard cruise ships still floating at sea.

A worldwide standoff between cruise companies and health authorities has left

approximately 100,000 crew stranded at sea. Many have spent more than a month self-isolating in cabins, unable to leave, and have lost their jobs during the pandemic.

On Sunday, a Ukrainian woman died after apparently jumping from the Regal Princess outside the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Dutch police confirmed the death of a 39-year-old woman. Princess Cruises, part of Carnival Corporation, said support was being offered to staff and the family of the deceased.

On the Navigator of the Seas off the coast of Miami, 15 Romanian crew started a hunger strike in protest at not being able to disembark. Royal Caribbean said the strike ended after a charter flight was arranged from Barbados later this month.

Many other ships remain marooned around the world. In the Philippines, Manila Bay has more than 20 cruise ships with around 5,300 staff on board waiting for clearance to disembark.

In Germany, police in the Germany port of Cuxhaven were called on board the Mein Schiff 3 last week after reports of disturbances. Nearly 3,000 crew members from several ships had been assembled onboard awaiting repatriation to numerous countries, but were told they would have to stay on the ship after nine people tested positive for Covid-19.

The deaths and conflicts have prompted renewed warnings about the mental health of crew stuck at sea waiting for permission to return home.

Satellite image of cruise ships, mainly from the Celebrity and Royal Caribbean lines, anchored 10 miles west of Coco Bay in the Bahamas. Photograph: Planet Labs Inc/AFP via Getty Images

Satellite image of cruise ships, mainly from the Celebrity and Royal Caribbean lines, anchored 10 miles west of Coco Bay in the Bahamas. Photograph: Planet Labs Inc/AFP via Getty Images

Cruise lines were managing to repatriate small contingents of crew members to some Caribbean countries by Tuesday, but even those efforts raised consternation in Haiti and Grenada after reports of some crew not being put into the required quarantines, according to reports in the Miami Herald.

Cruise companies have blamed strict rules from health authorities for not letting crew disembark. In and around US waters, 100 cruise ships with 70,000 crew are still waiting at sea, but the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently told the Guardian that some operators have opted to stay at sea, citing concerns about cost and potential legal consequences.

Crew members stranded at sea have said the experience has taken its toll on their mental health.

Will Lees, a Canadian who was hired to run art shows and gallery sales on the Norwegian Star starting last October, said the waiting and uncertainty have been deeply unsettling. He has not been on land since passengers left the ship on 14 March and has been shuffled between three ships to await repatriation. He was on the Norwegian Epic on Friday at dock in Miami, but has since been moved to a new ship that is now sailing him to Europe. From there he has been told he will be flown back to Canada.

“Each day you have no real purpose. It’s the same as the day before,” he said in a WhatsApp message sent from the middle of the Atlantic, somewhere near the Bermuda triangle. “You feel like you’re giving up your life and doing the same thing over and over again. It’s depressing.”

In response to concerns about the mental health of staff, Royal Caribbean said: “The health and safety of our crew is our top priority and we are working around the clock to make sure they get home safely. We have an employee assistance programme that crew are able to call 24 hours a day and is fully confidential.”

Carnival Corporation said: “We provide all employees complimentary access to our employee assistance programme (EAP), which includes a variety of services, and credentialed counsellors. In addition, our onboard medical team is trained to identify guests and crew who might need additional resources and support.”

Tui said it has since been able to send 1,200 crew on the Mein Schiff 3 home on charter flights carrying only workers who have tested negative.

“TUI Cruises was and is in daily contact with the ship’s management. We are aware of the tense situation of some crew members who had been waiting for their return journey for a long time and we try to support the crew in all matters in this uncertain situation.

“The ship’s management informs the crew on a regular basis: up-to-date information on the situation is communicated by the captain via shipboard announcements and is displayed on all screens on board for reading. In order to address and support the crew in this exceptional situation, TUI Cruises has – among other things – also initiated assistance in the field of maritime psychosocial emergency care for the crew on board as well as for the ones isolated on land.”

Caio Saldanha from Brazil in his cabin on the Celebrity Infinite. Photograph: AFP via Getty Images

Caio Saldanha from Brazil in his cabin on the Celebrity Infinite. Photograph: AFP via Getty Images

Prof Ann Kring, who chairs the psychology department at the University of California, Berkeley, said the long-running uncertainty and lack of control facing crews stranded on ships presents the sort of “horrific” situation that could cause anxiety in anyone.

“They are stuck, they have no information, they don’t know whether the person in the next room is sick or whether they will get sick or whether they ever get home,” she said, noting that crew members may also face loss of jobs and uncertain financial futures. “The limbo that they are in is not only anxiety-producing, it could be traumatic in the long term.”

She said getting people off the ships, so they could get the fresh air, exercise and healthy food recommended for everyone in isolation, would be a good start to helping them cope with the situation.

“It’s taking way too long,” she said.

Royal Caribbean also confirmed the death of a crew member on the Mariner of the Seas, currently stationed near the Bahamas, but said the death appeared to be from natural causes.

It said it had planned to have many crew members heading home last week, but its efforts were delayed by “external restrictions”.

Cruise ships anchored in Manila Bay in the Philippines. Photograph: Pcg/EPA

Cruise ships anchored in Manila Bay in the Philippines. Photograph: Pcg/EPA

“We had multiple charters ready for crew. However, due to external restrictions, crew members were not permitted to leave the ship and also could not take commercial flights,” a spokesperson said, adding that the company was working “around the clock” to get crew home.

Krista Thomas, a former cruise ship employee, has been running a Facebook group to update hundreds of crew members at sea about how to get home. Many have expressed concerns about their mental health.

“If they have a window to look out of, they’re looking out at this dark ocean – wondering when they’ll see land, when they’ll go home, how their family is doing, if they’ll be able to provide for them,” she said.

“When you’re sitting in a room with nothing to go to and no one to talk to, disconnected from your family, then it only takes something small to spiral.”